XTC Dive Center, Xcalak, MexicoContents of this Issue: XTC Dive Center, Xcalak, Mexico New Rules for Lithium-Ion Batteries on Airplanes Security Concerns for Diving in Malaysia Cuan Law, British Virgin Islands Hammerhead on the California Coast: “It Kept Coming At Me” Anything New at the DEMA Show? Getting Batteries for Old But Reliable Dive Computers Do Sport Divers Need a Spare Air? Carl Roessler, Steve Jobs and the “Maddened Attack” Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 face-to-face with crocodiles in the Yucatan from the November, 2015 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Diver: My latest trip of a lifetime, in theory, was to be a "close-in quickie." I would fly to Cancun with a group of friends, take a van to the small town of Xcalak, near the Mexico-Belize border, then take a dive boat to Chinchorro Banks to overnight in a fisherman's shack, where we were to snorkel with American crocodiles. I wasn't so sure it would happen, but wow, do I now have the open-jaws pictures to prove it. The six-hour flight to Cancun was a breeze, but the remaining transit made the day arduous. Having been told to meet the van driver "at the restaurant outside Terminal 3," we found it nearly impossible to get to Terminal 3 with all the construction. When we at last found the outdoor restaurant, we were told by other taxi drivers that our "unofficial" driver was not permitted to park there. They would take us (by taxi, of course) to where he had parked -- $20 for a three-minute ride. OK, but it seemed like a setup. The five-hour drive south to Xcalak and the XTC Dive Center was comfortable enough, but the farther south we went and the darker it got, the more unsettling it felt to be on Mexican highways and remote roads at night, considering State Department advisories about the dangers of traveling in Mexico outside regular tourist areas.

I awoke the next morning to calm seas and that unpleasant smell of rotting Sargassum, which proved more aromatic than the odor rising from the bathroom drains (I was given a drain stopper that held the septic tank smell at bay . . . until I used the facilities). The freshwater shower (rooms on the third floor had little more than a dribble) provided temporary relief from the cloying air. While the minimalist dive shop is labeled a five-star PADI dive center, I'd be pressed to give one star to the resort, though the food was OK. (There is other lodging in Xcalak, but I took XTC's suggestion to lodge at the Flying Cloud because it is adjacent to the dive shop.) After an eggs-cooked-to-order breakfast, our gear, along with the food, whatever beer and alcohol we divers bought in town, and supplies necessary for our overnight at a Banco Chincorro's fisherman's hut, was placed on the bottom of a maybe 25-foot dive boat by a small army of divemasters and resort trainees who were enrolled in an apprenticeship program that appeared to be a secondary source for resort income and staffing (the apprentices pay to learn, expecting to find jobs as divemasters elsewhere, though there is no elsewhere in Xcalak). XTC employs many townspeople, including the town's mayor as a boatman. Before our 8 a.m. departure, we were issued rain jackets for a rough crossing, then crashed through waves and wind, both of which flowed against us. The hard fiberglass bench seats caused most of us to end up so sore, we couldn't sit comfortably for the rest of the trip.

The islands of Chinchorro Banks are the northern end of the reef that runs south along nearly the entire length of Belize. It's the first point at which galleons from the Old World might strike reefs as they came to pillage the natives. Diving the wrecks would have to come another day, because we had come to go nose-to-nose with the crocs. The first task was to spearfish lionfish for croc bait. It was a good dive on healthy reefs, with a lot more lionfish than there should be. We returned to the shack with a Zookeeper, which safely contained nearly a dozen culled lionfish. The baiting began, well-advertised by the fishermen who replicated all the sounds and smells of cleaning the day's catch, just to get the crocodiles' attention. As I watched from the relative comfort of the hut, munching on a ham and cheese sandwich, our boatman tied two lionfish to a fishing line and tossed them in a high arc away from the boat, which he had repositioned near the mouth of a mangrove-bordered lagoon. No takers, so he repeated it again, and again and again ... for four hours. At the shack, they repeatedly filled buckets with water and poured it back into the sea, whistling and beating a club against the cutting table -- all normal sounds to tell the crocs that, "Hey, we're just cleaning fish, come and get some like you always do."

The short wait for the underwater appearance was electric, and I was nearly overcome with raw adrenaline-fueled excitement. All of a sudden, there she was, snapping at the lionfish, her jaw filled with huge rows of menacing teeth that seemed to extend two feet, all the way to her throat. The three of us stayed in a 15-foot-square area of white sand in three feet of water, while the croc stayed on a seagrass bank about a foot higher, only three feet away from us. The guides' lionfish casts were spot-on, causing the croc to turn repeatedly and open her jaws straight at us. Amazingly, I felt excited and safe, not nervous or fearful. For 25 years, I had been practicing my composure for the day I would be eye-to-eye with a "salty." (It's crazy, I know.) Everyone's turn in the water seemed to last mere seconds, and we rotated snorkelers again and again. The photo and video opportunities were perfect.

To watch the new arrival, we changed shifts in the water several times. She was bolder and more confident than the first, but to me, no more menacing than a shark. For the most part, she remained still, looking at us. In fact, she seemed curious and more interested in inspecting us than gobbling up the bait, which at times she just played with. Mathias said the crocs much prefer grouper, but lionfish are the only creatures they may legally harvest. When the second croc slipped off the bank and onto the sand, where we were positioned, Mathis would simply intercept her with his pole and guide her back to the grass. (He had told us he recognized these crocs from previous trips and knew their behaviors, so I felt confident in him.) After dinner -- excellent enchilada-style chicken and vegetarian casseroles and a green bean-casserole, finished with store-bought cookies -- three of us slept in hammocks in the fisherman's hut, two opted for air mattresses on the deck under the stars, and one slept on the boat. It was breezy and comfortable, but a brief rainstorm drove those outside to seek shelter under the roof. When the rain stopped, so did the breeze, allowing mosquitoes to feast on us the rest of the night -- even the 30-percent DEET bug spray was little help.

The next day, my buddies and I dived two very good, close-in sites, loaded with the "regulars" that inhabit these Mexican waters -- a large number of groupers, angelfish, butterflyfish, squirrelfish, green morays, barracuda and large lobsters. I was surprised how healthy the coral appeared. I finned through swim-throughs, as well as a one-way tunnel loaded with clouds of silversides. I twice encountered schools of three dozen tarpon, averaging five feet, and even a skittish manatee, the first the dive crew had seen in months. Our dives were 60 minutes long, 45 to 60 feet in depth with mild currents, 85-degree water and 40-foot visibility. Two divemaster trainees practiced hovering over us and keeping all divers in sight. Upon our return, the dive center's staff collected and rinsed our gear, while we enjoyed delicious chips, dips and drinks in the bar. The restaurant's limited menu offers tasty food, such as burgers and grilled chicken sandwiches, and they would most likely try to accommodate dietary restrictions, but only if informed in advance. This is not a crowded place. We bunked uncomfortably for the night once again, then hit the road for Cancun the next morning. The amazing encounters at Banco Chinchorro left all of us eager to share our feelings at being in the water with these magnificent animals. The very chance to swim with them easily negated the tedium of the long transits and the restless nights at the fisherman's shack and the resort. We're eager to return for another go. The response I get when I show my photos and tell my stories reinforces the fact that this was, indeed, a trip of a lifetime. Our undercover diver's bio: A.T.H. says, "I am a terminally mature adult diver who struggles with the reality that, apparently, I've not been everyplace and done everything as I had earlier imagined, but wow, where I have dived and what I have seen! I'm the dive coordinator for a fun group of like-minded adults, mostly underwater photographers, who have short bucket lists and realize that whining about delayed flights and overweight fees is futile."

-- A.T.H. |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

After pulling

into XTC Dive Center

at 10:30 p.m., we

were greeted by both

the dive shop manager

and the manager

of the Flying

Cloud Hotel, where

XTC is based. We

were to spend the

night here, before departing in the morning to the islands

of Banco Chinchorro, 36 miles into the

Gulf of Mexico. I was ushered to my room,

where it took a half-hour for the August

temperature to drop to 85 degrees, with

humidity to match. A single oscillating

fan provided the only relief; the breeze

outside was light, but enough to carry in

the stench of rotting Sargassum seaweed,

which extended out from the shoreline for

25 yards. My Spartan room had a nightstand,

armoire and a comfortable bed, but

that offered no respite from being bathed

in so much heat and humidity that I felt

like I had returned to my mother's womb.

Thanks to a dose of Ambien, I eventually

got some shut-eye.

After pulling

into XTC Dive Center

at 10:30 p.m., we

were greeted by both

the dive shop manager

and the manager

of the Flying

Cloud Hotel, where

XTC is based. We

were to spend the

night here, before departing in the morning to the islands

of Banco Chinchorro, 36 miles into the

Gulf of Mexico. I was ushered to my room,

where it took a half-hour for the August

temperature to drop to 85 degrees, with

humidity to match. A single oscillating

fan provided the only relief; the breeze

outside was light, but enough to carry in

the stench of rotting Sargassum seaweed,

which extended out from the shoreline for

25 yards. My Spartan room had a nightstand,

armoire and a comfortable bed, but

that offered no respite from being bathed

in so much heat and humidity that I felt

like I had returned to my mother's womb.

Thanks to a dose of Ambien, I eventually

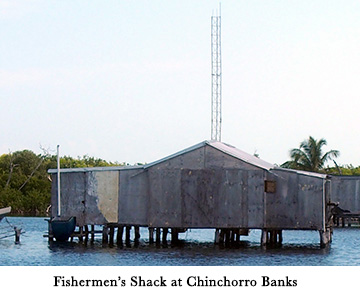

got some shut-eye. Two hours later, we pulled up to a fisherman's shack on stilts, from

which we would hopefully mount our snorkeling adventure with the crocodiles.

The loose assemblage of wood and plastic under a corrugated metal roof was

accessorized by a sleeping room strung with hammocks, a cooking area with a

gas stove, a fish cleaning area that doubled as a meeting place, and a storage

compartment with a hole in the floor

(if you have to ask what it's for, you

probably shouldn't do this trip, though

there was a questionable-looking compost

toilet, which only one of us used). I

rinsed off with rainwater from 55-gallon

drums, deferring to the drinking water and

soft drinks transported with us in a huge

ice chest. Food for our stay amounted to

snacks and pre-prepared (and quite good)

casseroles from the resort.

Two hours later, we pulled up to a fisherman's shack on stilts, from

which we would hopefully mount our snorkeling adventure with the crocodiles.

The loose assemblage of wood and plastic under a corrugated metal roof was

accessorized by a sleeping room strung with hammocks, a cooking area with a

gas stove, a fish cleaning area that doubled as a meeting place, and a storage

compartment with a hole in the floor

(if you have to ask what it's for, you

probably shouldn't do this trip, though

there was a questionable-looking compost

toilet, which only one of us used). I

rinsed off with rainwater from 55-gallon

drums, deferring to the drinking water and

soft drinks transported with us in a huge

ice chest. Food for our stay amounted to

snacks and pre-prepared (and quite good)

casseroles from the resort. Finally, they came. Well, at least one came, a 10-footer in hot pursuit

of the boatman, who was driving slowly, a lionfish in tow. As the boat

returned to the fishing shack, Mathias, our excellent divemaster, briefed us

on how to proceed. He would get into the water first, holding upright a sixfoot

wooden pole, our only "protection." Two snorkelers would follow, positioning

themselves alongside each of his shoulders. Mathias told us to face

the crocodile and never drop our faces or bodies down or away from it. The

croc might think we were submissive or intimidated, and strike -- and we

would be no match.

Finally, they came. Well, at least one came, a 10-footer in hot pursuit

of the boatman, who was driving slowly, a lionfish in tow. As the boat

returned to the fishing shack, Mathias, our excellent divemaster, briefed us

on how to proceed. He would get into the water first, holding upright a sixfoot

wooden pole, our only "protection." Two snorkelers would follow, positioning

themselves alongside each of his shoulders. Mathias told us to face

the crocodile and never drop our faces or bodies down or away from it. The

croc might think we were submissive or intimidated, and strike -- and we

would be no match. Toward the end of the first hour,

I heard one of the deck hands call out, "Heads up, here comes another." A

larger croc, 11 feet and much heavier, moseyed in. Her first action was to

establish her dominance over the smaller croc by attempting to bite her in

two, but the smaller one, with a powerful swipe of her tail, went airborne,

leaping from the water to escape the other. She then took up a position 50

feet away, while her buddy came in to see what smelled so edible.

Toward the end of the first hour,

I heard one of the deck hands call out, "Heads up, here comes another." A

larger croc, 11 feet and much heavier, moseyed in. Her first action was to

establish her dominance over the smaller croc by attempting to bite her in

two, but the smaller one, with a powerful swipe of her tail, went airborne,

leaping from the water to escape the other. She then took up a position 50

feet away, while her buddy came in to see what smelled so edible. After breakfast -- egg, bacon and cheese casseroles, fresh fruit, granola

and yogurt -- we repeated our lionfish hunt at a different dive site.

Afterward, the crew spent four hours in

a valiant baiting effort, but the crocodiles

stayed home. Oddly, I was only mildly

disappointed, still riding the amazing

high of my encounters the day before. Late

afternoon, the crew cleaned up and loaded

the boat for our return to Xcalak. Still

sporting bruised bums, we stood or lay

on the deck or seats to avoid additional

trauma to our battered backsides. With

following seas, we returned in 90 minutes.

After breakfast -- egg, bacon and cheese casseroles, fresh fruit, granola

and yogurt -- we repeated our lionfish hunt at a different dive site.

Afterward, the crew spent four hours in

a valiant baiting effort, but the crocodiles

stayed home. Oddly, I was only mildly

disappointed, still riding the amazing

high of my encounters the day before. Late

afternoon, the crew cleaned up and loaded

the boat for our return to Xcalak. Still

sporting bruised bums, we stood or lay

on the deck or seats to avoid additional

trauma to our battered backsides. With

following seas, we returned in 90 minutes. Divers Compass: The croc-diving package, with scuba dives and

transportation, ran me $1,050 . . . While I brought my own

gear, XTC has adequate rental gear, including a BCD, regulator

and computer for $25 a day . . . English is widely spoken . .

. My group ponied up 10 percent of the trip cost to be divided

among all staff, and we passed out a few individual tips . . . Two of our group stayed at the Casa Carolina, and while there was no air-conditioning,

the resort was much nicer; Costa de Cocos and Playa Son Risa are

better hotels, but you may need to arrange transportation . . . Xcalak is a

mix of sleepy fishing village locals, expats and random 20-something adventurers

from around the world; there is no phone/cell service, and Internet service

is patchy . . . Website -

Divers Compass: The croc-diving package, with scuba dives and

transportation, ran me $1,050 . . . While I brought my own

gear, XTC has adequate rental gear, including a BCD, regulator

and computer for $25 a day . . . English is widely spoken . .

. My group ponied up 10 percent of the trip cost to be divided

among all staff, and we passed out a few individual tips . . . Two of our group stayed at the Casa Carolina, and while there was no air-conditioning,

the resort was much nicer; Costa de Cocos and Playa Son Risa are

better hotels, but you may need to arrange transportation . . . Xcalak is a

mix of sleepy fishing village locals, expats and random 20-something adventurers

from around the world; there is no phone/cell service, and Internet service

is patchy . . . Website -