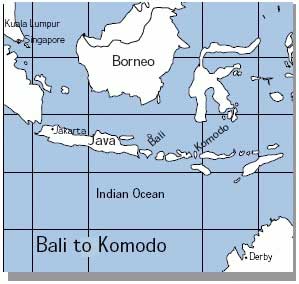

Chasing the Dragons of KomodoContents of this Issue: EQUIPMENT TIP —THE NEW ZEALAND SAFETY SAUSAGE Don’t Even Think About It: Installment Two Emergency Breathing from Your BC How to Emergency Breathe From a BC TRAVEL TIP HAWAII: WHERE HAVE ALL THE MANTAS GONE? Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 Aboard the Sea Contacts I from Bali to Komodo from the September, 1999 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Divers: Before every dive I asked myself the same questions: Would the current be fierce or imperceptible? Would I luxuriate in balmy water or freeze my butt off? Would the water be gin-clear or murky as a day off New Jersey? Would I see exciting critters, like pygmy sea horses, ornate ghost pipefish, turtles, and mantas, or would I swim among the ubiquitous, yet stunning, assortment of Indo-Pacific tropicals? I knew before I came to the diving frontier of Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands that I was heading to the epicenter of marine biodiversity. However, I hadn’t expected that diversity to permeate every aspect of my dives. Still, in retrospect, it only seems fitting that the diving on this run from Bali to Komodo was as wild and unpredictable as the place itself. Indonesia’s my favorite dive destination, and diversity’s not the only reason. It offers phenomenal diving over an enormous area. Its 7000 islands (and almost as many separate cultures) offer unusual land excursions. And it’s far from the diving crowds. Since I get more for my diving money with ten days in

Indonesia than twenty on Grand Cayman, I opened my wallet

for an April trip aboard the Sea Contacts I, a 112-foot

traditional Buginese sailing ship. We departed late in the

day against a strong head current for our longest overnight

journey. It was 9 a.m. before we reached our first

dive spot: Angel Reef, off the island of Moya in the center

of the Indonesian Ring of Fire. This was a pictureperfect

place to start: several conic volcanoes surrounded

us, a truly incredible vista. While Sea Contacts is a new operation, its diving director, Larry Smith, is long on Indonesian experience and highly respected by many Undercurrent readers, who follow him wherever he goes. A short, red-headed, barrel-chested, Tyler, Texas, native, Larry worked at Little Cayman’s Pirate’s Point before fixing on various Indonesian venues over the last several years. His eagerness is infectious: he’s stayed so untarnished over the years that I’d swear Larry’s jade-proof. At first blush, this two-masted schooner doesn’t seem appropriate for a dive boat (though the sails do provide good photo ops), but actually the cruise is engine-driven all the way. The boat’s interior has lots of lush, dark wood that’s still shiny with varnish. The cabins, each with its own porthole and en-suite bath, are roomier than those of many other live-aboards. However, the bunk-bed layout is poor for storage and sleeping, and I had to turn sideways to shave over the sink. Each cabin had a remotecontrolled a/c unit powerful enough to freeze me out, although they had a nasty habit of switching off in the middle of the night. The boat also had a serious roach problem when I was there, one that’s supposedly been remedied since. Up till a short time before departure, I was the only diver signed up. Incredibly, Sea Contacts still guaranteed the trip. (Hell, some land-based operations won’t even go on a night dive if only four divers sign up.) A Burmese couple finally joined us after their trip on the Madivaru 7 was canceled at the last minute because, ironically enough, there weren’t enough passengers. Obviously we had plenty of space, but even at its 12-diver capacity, Sea Contacts would be a roomy craft. The lounge and dining area was cool, spacious, and well-lit. They had a small collection of videos (although their VCR was broken) and some books, including eight marine ID books and collections of underwater photos. The middle deck with the wheel house and crew’s quarters has a large shaded area that’s good for lounging, while the top deck was for sun-lovers, sunset aficionados, and nighttime stargazers. One side of the main deck was outfitted with cabinets and a work area for camera buffs that would be sorely tested with 12 heavy-duty photographers aboard. Camera amenities included a camera rinse bucket and a good-sized inside charging station to handle those ubiquitous rechargeable batteries. But there was no film processing (a bummer since I didn’t find out till after the trip that one of my lenses was acting up). Larry, off on business, didn’t join us till 2/3 of the way through the trip. The American divemaster, David Espinosa, a wiry, enthusiastic 23-year-old, had only been working with Larry about 6 months and was nervous about running the show. He was assisted by a temporary instructor, Tony Rhodes, and a crew of 12 friendly, helpful, non-English-speaking Indonesians who’d help me get up the plank and out of my gear after a dive. Their perennial smiles spoke volumes about how much they enjoyed plying their trade. Overall, things worked as they should and on schedule.

Purbo’s real blowouts were his 6-8 course dinners. One night’s menu, a candlelight,

white-tablecloth affair served top-deck, consisted of tuna steak, spaghetti

Bolognese, nasi goreng, two salads, broccoli, homemade banana bread, and

ice cream. Other meals included chicken, steak, pork dishes and killer Thai red

chicken curry. Drinks, except imported liqueurs, were free. Great meals, at

least, were predictable, even if the diving wasn’t.

Take a dive that sounds like paradise: Highway to Heaven, off the volcanic

island of Gila Banta, featuring conditions unusual for this part of Indonesia: no

current and 100' vis. The water was just 79°, but when I backrolled off the Zodiac

and saw the fish life, my excitement raised it another five. Marine life was

more varied and prolific than anyplace I’ve been. Soft corals and schools of tropicals emblazoned the wall. Red tooth triggerfish intermingled with fusiliers

and unicornfish. Large, yellow coral had sizable schools of goldfin and redfin

anthias dancing around, illuminated by bright sunlight shining through the clear

blue water. A school of dogtooth tuna cruised nearby; a 3' green sea turtle paddled

below. Two whitetip sharks swam leisurely below while an eagle ray glided by. The

wall soon flattened to a gentle slope with even more fish. I preferred diving from the main boat, which had retractable steps that were easy to board. But these waters didn’t allow many such opportunities, so we dove from two inflatables. Five-minute rides were about as far as we got from the mother ship. Diving rules? “Don’t do anything stupid.” “Limit your dives to 70 minutes.” Safety stops were recommended, and we were free to dive alone or join the guide. David briefed us before each dive, but I seldom saw him in the water. (He seemed to think we wanted him to stay out of our way.) Larry, of course, was keen on finding and pointing out obscure critters. We spent most of the ten-day cruise diving off Komodo and Rinca Islands, which were even more wild and woolly. Through the Komodo straits, the water boiled with eddy currents, forcing us to dive in protected areas like Horseshoe Bay, where the water was cooler. At Cannibal Rock, in 73° water with 30-foot vis, I struggled getting to the bottom in the one-knot current. Once there, the reef was alive with invertebrates, loads of soft coral, and crinoids in a thousand colors. Two ornate ghost pipefish danced around red soft coral, but I had trouble shooting in the current. I spotted a sea apple with its candy-apple red outside shell and arms protruding from the top. While focusing on an orangutan crab in bubble coral, I noticed two beautiful, 3" white, yellow, and brown nudibranchs. Still fighting the current and getting colder, I spotted a fire urchin housing both an emperor shrimp and zebra crabs. But the cold got me. Next time, I vowed, I’d bring more rubber. On my second dive here the current had disappeared and vis had doubled, revealing an incredible variety of weird sea life: dozens of species of nudibranchs, zebra crabs, pygmy sea horses, pygmy cuttlefish, flatworms, mushroom coral pipefish, blue ribbon eels, and mantis shrimp. It reminded me of Kungkungan Bay in northern Indonesia, but with much better vis and coral. Occasionally there were bigger critters: a few Napoleon wrasse, large Jewfish, whitetips and one bull shark, a few mantas, and schools of jacks. You can’t come to this part of the world without doing a good bit of onshore exploring as well. I spent one day touring Bima’s open market, where we foreigners were the biggest attraction. It was colorful and crowded, and I was immersed in the smells of fish and spices. From there we rode in a tiny horse-drawn mini-stagecoach to the Sultan’s Palace, an immense old wooden structure. At Komodo Island, we took an inflatable to the beach where, before setting foot, we looked around nervously for the legendary Komodo dragons. For protection, our guide wielded a flimsy 6' forked stick. Soon, we spied five large dragons, the largest about 9', at a cluster of buildings. “Go ahead and approach them,” our guide told us, “but not too closely. And don’t trap yourselves with a building at your back.” Despite the warnings, the dragons suffer from a reputation that’s much worse than they are. They’re generally lethargic, particularly during the heat of the day, and only eat every few days. We searched for more beasts during a beautiful hike with views of the bay that turned up many butterflies, flying, four-inch lizards, and half a dozen more docile-looking dragons. We didn’t encounter the real monsters of the island, truly voracious and obviously starved for tourists, until we reached the end of our walk: a bevy of hawkers who outnumbered us 10-to-1 and were determined to sell each of us dozens of pearl necklaces, carved wooden dragons, and other trinkets. Later, after a dive near the park, we went ashore on Komodo’s gorgeous, red-sand beach for a barbecue white-tablecloth style. The crew built a hearty bonfire, and we had a spectacular dinner of grilled steak and fish accompanied by a pleasant wine. We finished the week with four dives off Bali. At East Point I came around a corner at 80' and hit current near the slope that pulled me downward. Not only did I kick up: I fully inflated my BC, and it still pulled me deeper. I grabbed rocks on the slope and, kicking all the way, pulled myself out of the downcurrent. Later we dove at the famed Liberty ship Tulamben, one of the truly great fish spots in the world. There Larry coaxed a huge stonefish out from under a piece of wreckage, then did his jack call, something like a loud underwater raspberry, enveloping us in a 500-fish school of horse-eye jacks. All told, I made 31 dives, 6 at night. Was the diving what I’d expected? I didn’t expect such temperature variation and came unprepared. When I wrote the Sea Contacts office, I’d asked about the water temperature and was told to expect 78°-86° water. By the time I got there a month later, it had cooled off a bunch. I found water temps between 73° and 84°, and 73° feels a helluva lot colder than 78° to me! But I’ve learned to accept the unexpected, and indeed there’s some incredible diving here. While the boat, service, meals, and accommodations soften this wild-and-woolly frontier, the diving on this archipelago changes with the currents. You have to be willing to go with the flow without whining. Even if the Komodo dragons don’t get you, this isn’t a trip for the unadventurous. — W. D. 40

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

The 84° water felt great,

and the 80' vis revealed trevally jacks, sweetlips, and a multitude of tropicals among healthy

and colorful soft corals. Later that

evening we watched thousands of flying

foxes departing the island in clouds,

hungry to feast on the fruits of

neighboring Sumba.

The 84° water felt great,

and the 80' vis revealed trevally jacks, sweetlips, and a multitude of tropicals among healthy

and colorful soft corals. Later that

evening we watched thousands of flying

foxes departing the island in clouds,

hungry to feast on the fruits of

neighboring Sumba. The dining was superlative. Chef

Purbo, straight out of a Sheraton Hotel

job, served up six-course meals exhibiting

real culinary mastery. Each morning

the cabin stewards, Nyoman and

Gede, served a mini-breakfast before

the first dive and took orders for the

full breakfast. The “mini” consisted of

fresh fruit (oranges, bananas, and

pineapple), orange or apple juice,

pancakes, cereals, toast and coffee or

tea. For the main breakfast I’d often

opt for Indonesia’s national dish, that

hodgepodge of chopped peanuts, vegetables,

meats, fried eggs, and sundry

leftovers that’s called “nasi goreng”

when made with rice, or “mie goreng”

when made with noodles. Pancakes, omelets,

bacon, and other standard fare were available. Lunch, generally served

after the second dive, was a five-course affair with Indonesian or western salad,

cooked vegetables, steamed rice, mixed fruit, and a saté (whether spicy, barbecue-

ish bits of pork, beef, lamb, prawn, chicken, or tuna), and a tasty dessert.

Fruit, cookies, and hors d’oeuvres were generally available after dives.

The dining was superlative. Chef

Purbo, straight out of a Sheraton Hotel

job, served up six-course meals exhibiting

real culinary mastery. Each morning

the cabin stewards, Nyoman and

Gede, served a mini-breakfast before

the first dive and took orders for the

full breakfast. The “mini” consisted of

fresh fruit (oranges, bananas, and

pineapple), orange or apple juice,

pancakes, cereals, toast and coffee or

tea. For the main breakfast I’d often

opt for Indonesia’s national dish, that

hodgepodge of chopped peanuts, vegetables,

meats, fried eggs, and sundry

leftovers that’s called “nasi goreng”

when made with rice, or “mie goreng”

when made with noodles. Pancakes, omelets,

bacon, and other standard fare were available. Lunch, generally served

after the second dive, was a five-course affair with Indonesian or western salad,

cooked vegetables, steamed rice, mixed fruit, and a saté (whether spicy, barbecue-

ish bits of pork, beef, lamb, prawn, chicken, or tuna), and a tasty dessert.

Fruit, cookies, and hors d’oeuvres were generally available after dives.  Should I shoot the two

coral groupers near the 4' table coral with its school of humbugfish bobbing up and

down with my exhaust, or try to capture the schools of long fin bannerfish and

surgeonfish near a large bommie covered with crinoids in a painter’s palette of

colors? Or just gawk at the banded sea

snake swimming below? Incredible. But then

came dive two here: I was bounced around

by wild currents, had half the visibility,

and saw far fewer fish. Chalk one up for

unpredictability.

Should I shoot the two

coral groupers near the 4' table coral with its school of humbugfish bobbing up and

down with my exhaust, or try to capture the schools of long fin bannerfish and

surgeonfish near a large bommie covered with crinoids in a painter’s palette of

colors? Or just gawk at the banded sea

snake swimming below? Incredible. But then

came dive two here: I was bounced around

by wild currents, had half the visibility,

and saw far fewer fish. Chalk one up for

unpredictability. Diver’s Compass: Sea Contacts: phone 62 361 725 430; fax 62 361

725 431; e-mail:

Diver’s Compass: Sea Contacts: phone 62 361 725 430; fax 62 361

725 431; e-mail: