Manta Lodge / World of Watersports, TobagoContents of this Issue: Manta Lodge / World of Watersports, Tobago Revisiting a Dive Incident from 15 Years Ago California Puts the “Rub” on a Shady Fish Collector Travel Tips & Helpful Dive Hints: Part I Brits Dive Hard and Drink Hard Serious Dive Gear, But Where’s the Fun? Diver Makes Fatal Mistake During Typhoon Haiyan Sad but Foolish Cave Diving Deaths This Dive Resort is Taking a Stand Husband Sues PADI for Wife’s Death from Carbon Monoxide Falling Stars: Mass Starfish Deaths on the West Coast The Top 10 Dive Resorts -- for Non-Divers, Perhaps Sounding Off on the Seahorse's Plight Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 a tiny isle with some of the Caribbean’s best diving from the January, 2014 issue of Undercurrent

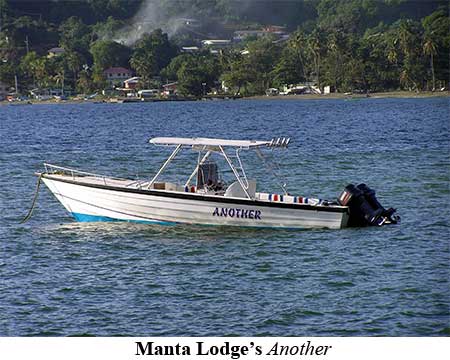

Dear Fellow Diver: When I told Ben Davison I was headed to Tobago -- that tiny partner of Trinidad, just 50 miles off of Venezuela's coast -- and would do a story on the diving there, he got grumpy. Having been there a couple times, he considered it one of the great Caribbean dive spots, and he loved the island as well. He wanted to return and write an article himself, but there were too many other spots on his wish list; however, Undercurrent readers ought to know about Tobago. "Oh, go ahead, damn it," he told me. Back-rolling off the 32-foot dive vessel Another into the Coral Gardens at Kelleston Drain, I was in a bubbly mush of seawater caused by an active ocean. But a few feet down, with no current, the vista opened up to a seascape of dozens of large azure vase sponges, up to five feet tall. The dense coral coverage showcased large numbers of colorful tropical fish, as well as the largest brain coral in the world (so they say) that is several centuries old, and 10 feet tall by 16 feet wide -- impressive and incredible! A spotted eagle ray cruised by. Queen, French and gray angelfish abounded in the 84-degree water. Ben was right.

Clyde, gracious to his core, occasionally shifted from his relaxed pace into dance steps of a bygone era as he glided across the floor. He made sure there was a stock of red wine and gin-and-tonics to suit my preferences. He knew I liked fish, so generous tasty portions were presented at most lunches and dinners. Fresh lobster one night was delicious, as were the shrimp another evening. It was a toss-up who would cook breakfast for me -- Clyde or the friendly receptionist, Julia. There was always fresh star fruit and tiny bananas ("silky figs" is the local term) from their trees, accompanying an omelet and toast. The cook only came to prepare my 7 p.m. dinner.

On my first day, I was the only diver. On the other days, Martin and I were accompanied by divers from Trinidad, Rick, their dive instructor who Sean had trained, and an experienced diver from England. Tobago, by the way, is a throwback in time, so time is flexible. Yes, my divemaster arrived at 8:30 a.m. as promised, but we had to wait -- and wait -- for the others. Tanks and gear are loaded in a pickup truck for the five-minute ride to the dock. Captain Stilton, who has been with this organization from boyhood, takes great pride in keeping the new dive boat in excellent condition. Oddly, the crew does not deem the ladder safe for divers because it's within inches of the two 140-hp engines. So I exited the water by handing up weights and BC, then had to launch myself into the boat by sheer power, or wait for the sure arm-grasp assist by Silton. Awkward, yes, but getting into the boat was easy and painless. September often brings slack current to Tobago, which opens areas sometimes impossible to dive because of high waves and unmanageable current. From a hill outside the sleepy town of Charlotte on the island's north end, I gazed at the famous trio of dive sites, Sisters, London Bridge and Giles. Diving there did not happen -- four experienced divers were needed for the trip. I was disappointed, but still had 10 great dives in the Speyside area. There was only a hint of current at Bookends rather than the common ripping rides. I spotted a few elusive cherub fish, along with a flameback angelfish. Deeper, the strawberry vase sponges were spectacular against a backdrop of sea plumes and yellow tube sponges. Dropping down into a protected "amphitheater," I saw large lobsters that didn't bother to hide. Overhead, silvery tarpon schooled. One advantage of being a skilled diver with no newbies around is that you may get to dive the serious sites, which I did for two days with Sean. (I want to say here that I did not confess to my Undercurrent mission or try to curry favors, but I've learned that when one scoots off to remote sites lacking PADI Five-Star dive stores coaxing in people to breathe through a regulator at the bottom of a pool, you can find some private dives.) Back-rolling with negative buoyancy at Black Forest, I swooped over a huge area of up to 12-foot-tall bushy black coral on the sloping valley wall. At 158 feet down (yes!), I noticed a slight "narced" feeling; at 163 feet, we began gradually ascending. We stayed deep but never below three minutes to decompression time. The evening before, Sean and I had discussed the importance of knowing one's at-depth air consumption, nitrogen consumption and the relationship to decompression, so this was simply an enjoyable challenge. At Flying Manta, I was forewarned to stay close to the wall to avoid a current that could suck a diver into the "washing machine" and spit him out at 140 feet. But there the current was less than half a knot, if that, and waves topside were but a foot. Nearly a dozen scorpionfish, secretary blennies and a juvenile burrfish the size and shape of a little fingernail were memorable. These waters have an abundance of nutrients, making them a breeding mecca. At times there were thousands of fry no larger than rice grains, and so many that it could be disorienting. Shimmering water caused by mixed currents affected visibility at times on many dives. The visibility was a cloudy greenish for the first six feet, due to the flow of the Orinoco, the largest river in Venezuela. Below that layer, where it became warmer, the visibility was clearest within 30 feet, but seeable to 80 feet. Further out, around Little Tobago, it was a clear 80-plus feet.

Wanting to get a feel for Tobago's Caribbean diving, I went to the southern end to stay at the relatively upscale Turtle Beach Resort. My room had TV and internet, and it faced the ocean, large circular pool, Jacuzzi and swimup bar. There were about 40 other guests, mostly British. The reasonable allinclusive rate included buffet meals -- plentiful but nothing to brag about -- and drinks, even alcoholic ones. Dress for dinner? Well, hard to pull off for funky divers, but "smart-casual" meant long pants and collared shirts for the men, and tropical-weight dresses were the choice for most women. Local musicians often played. While the hotel has a friendly dive shop, I elected to continue my diving with Sean's World of Watersports. Tooley, my dive guide, picked me up in his truck and drove 15 minutes to the dive shop at the fancy Magdalena Resort. The park-like drive into the resort was enhanced by Tooley stopping to point out at least a dozen unique birds. After picking up Marvin (who would serve as captain), tanks and gear, another 15 minutes brought us to Pigeon Point and its 38-foot fiberglass boat (a little elbow grease would do wonders to spiff up this craft) with tank holders in the center, and friendly to handicapped divers with a drop-down side entry. From there, it was only several minutes to our dive sites. I was the only diver. Snacks of cookies and crackers were available during surface intervals, as was bottled water, same as at Speyside.

The large rocks of the nearby Mount Irvine Wall formed narrow swim-through canyons. The area had so much to see that sometimes I didn't know where to focus. After I saw the queen and French angel juveniles and a spotted drum, I knew it would be a good dive. Tooley and I took a very slow pace. Inside one crevice, we watched a black mantis first stick his head around a rock; patience won out as he eventually emerged. A green moray resided deeper in the crevice, and a spiny spotted lobster peered out from nearby. A rock beauty added nice contrast to the splotched brownish oyster toadfish. We watched two small crab in a mating mode, with one of them, presumably the male, rising up and weaving on his legs while he waved his claws. The female responded with some waving of her own. Emerging from the wall canyon, we were met by hundreds of Creole wrasse. After the dive, Marvin dropped me off at Turtle Beach Resort and transported my gear to the shop, where they washed and stored it for the next day. At the Extension, a three-foot Spanish mackerel curiously approached. Dozens of silvery boga schooled above. A Caribbean king crab that seemed comparable in size to an Alaskan king crab walked upside down on the ceiling of a reef shelf. In the open, a porcupinefish made a beeline toward me, stopping a foot away to stare. I waited a few minutes to see who was going to move first. I gave in, and the puffer slowly came alongside and swam with me for a few more minutes. Rounding out the special sightings here were juvenile vieja, flame scallops and the golden hamlet, not often reported in this part of the Caribbean. My last dive in Tobago was a lark. We went to Dutchman's Beach Reef in Mount Irvine Bay. While Marvin scrubbed the barnacles off the boat's bottom, Tooley and I went treasure hunting in the sand near the two protruding canon barrels of a 19th-century warship wreck. Our fanning the sand revealed two old encrusted bottles, lots of ballast and some pieces of unidentifiable metal. I took time around the site to enjoy an octopus in a hole and a female lancer dragonet. Atlantic-side diving is spectacular, the Caribbean side much less so with regards to corals, sponges and visibility. However, the treasures of fish and critter sightings in Mount Irvine Bay were well worth a few days of exploration. Tobago is forested and tropical; humidity was high, with air temperatures in the mid-80s. According to Sean, the driest time of year with the clearest waters and highest visibility is March through May. This is also the time for some of the strongest currents and mantas, too. I hit it at slack tide so that no dive sites were out of bounds due to current and waves. Tobago is below the hurricane belt, so it's a good autumn alternative to the Caymans, the Bahamas and Belize. -- J.D.

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

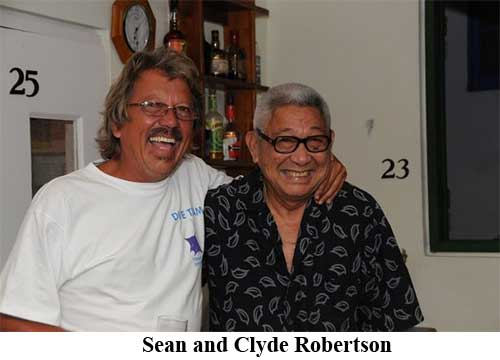

With luggage in

hand, I exited the

small Tobago terminal

on a balmy September

night at 11:30 p.m.

Clyde Robinson was

holding a sign with

my name. Ninety minutes

and 26 miles

later, over winding

and potholed roads,

I arrived at Manta

Lodge in Speyside,

a tiny village on the Atlantic side of the island

with a few restaurants, sheep, and

a high school. The lodge is base

for Sean Robinson's Tobago Dive

Experience, and he also operates

World of Water Sports on the southern

end of the island. Teaching diving

at the International School in

Trinidad (for free) consumes a lot

of his time. Sean's counterpart is

his father, Clyde, who has a more

practical approach to business, while

his son's passion is all things diving.

They are both characters of the

first order.

With luggage in

hand, I exited the

small Tobago terminal

on a balmy September

night at 11:30 p.m.

Clyde Robinson was

holding a sign with

my name. Ninety minutes

and 26 miles

later, over winding

and potholed roads,

I arrived at Manta

Lodge in Speyside,

a tiny village on the Atlantic side of the island

with a few restaurants, sheep, and

a high school. The lodge is base

for Sean Robinson's Tobago Dive

Experience, and he also operates

World of Water Sports on the southern

end of the island. Teaching diving

at the International School in

Trinidad (for free) consumes a lot

of his time. Sean's counterpart is

his father, Clyde, who has a more

practical approach to business, while

his son's passion is all things diving.

They are both characters of the

first order. Only the next morning did I see

across the road the beautiful views

of Goat Island and Little Tobago

Island. In the flowering trees and

bushes, hummingbirds zipped crazily.

Manta Lodge exudes gracious Caribbean

charm and the wear of a salty environment. There is a small pool at the

lodge, doubling for training divers and cooling off. With no doors to hinder

entry to the reception, dining room and bar area, the openness is welcoming.

A mother pooch and her two teenage pups eagerly greet visitors; so does

Clyde, who has a ready wave and smile. From Clyde's numerous stories, I gather

that the 90s was the heyday for the 22-room lodge, with laughing guests

ready to enjoy world-class diving or birding, and recapping their day at the

Lodge's Moray Eel bar. In contrast, I was the only guest for four of my fivenight

low-season stay. In the middle of the night when the wind blew open

my patio door, I felt the lodge's emptiness. However, the soothing sounds

of waves gently crashing, birds calling and frogs singing lulled me back to

sleep. All rooms face the ocean, and back onto the rainforest. My room was

clean and comfortable, with a king and single bed, desk, lounge chair, air

conditioner, ceiling fan and plenty of hot water. The lodge needs a lot of

repairs and updating, but it has that certain Caribbean charm.

Only the next morning did I see

across the road the beautiful views

of Goat Island and Little Tobago

Island. In the flowering trees and

bushes, hummingbirds zipped crazily.

Manta Lodge exudes gracious Caribbean

charm and the wear of a salty environment. There is a small pool at the

lodge, doubling for training divers and cooling off. With no doors to hinder

entry to the reception, dining room and bar area, the openness is welcoming.

A mother pooch and her two teenage pups eagerly greet visitors; so does

Clyde, who has a ready wave and smile. From Clyde's numerous stories, I gather

that the 90s was the heyday for the 22-room lodge, with laughing guests

ready to enjoy world-class diving or birding, and recapping their day at the

Lodge's Moray Eel bar. In contrast, I was the only guest for four of my fivenight

low-season stay. In the middle of the night when the wind blew open

my patio door, I felt the lodge's emptiness. However, the soothing sounds

of waves gently crashing, birds calling and frogs singing lulled me back to

sleep. All rooms face the ocean, and back onto the rainforest. My room was

clean and comfortable, with a king and single bed, desk, lounge chair, air

conditioner, ceiling fan and plenty of hot water. The lodge needs a lot of

repairs and updating, but it has that certain Caribbean charm. But back to the diving. Japanese

Gardens touts two of the second-largest

brain corals. Some, so old and large, collapse

on one side. This site rivals the

beauty of the Coral Gardens in carpet-like

coverage of corals and sponges. There were

two enormous - about eight feet -- coral

branching "trees," and schools of dozens

of Creole wrasse with their dark purple

heads, shading to yellow, then red toward

the lower body and tail. Bicolor damselfish

outnumbered the other smaller fish,

with brown chromis a close second. Looking

closely, I spotted several lettuce leaf slugs. We then headed to Kamikaze, a cut between two large boulders, where

the current usually rocks. No current, so we leisurely explored the soft yellow

corals in a way seldom possible. Martin, my dive guide, said he had not

seen it this calm in 10 years. At Cathedral, we slowly finger-walked in the

sand, and viewed the skittish and rare giraffe garden eels, with their yellowish

bodies and black spots.

But back to the diving. Japanese

Gardens touts two of the second-largest

brain corals. Some, so old and large, collapse

on one side. This site rivals the

beauty of the Coral Gardens in carpet-like

coverage of corals and sponges. There were

two enormous - about eight feet -- coral

branching "trees," and schools of dozens

of Creole wrasse with their dark purple

heads, shading to yellow, then red toward

the lower body and tail. Bicolor damselfish

outnumbered the other smaller fish,

with brown chromis a close second. Looking

closely, I spotted several lettuce leaf slugs. We then headed to Kamikaze, a cut between two large boulders, where

the current usually rocks. No current, so we leisurely explored the soft yellow

corals in a way seldom possible. Martin, my dive guide, said he had not

seen it this calm in 10 years. At Cathedral, we slowly finger-walked in the

sand, and viewed the skittish and rare giraffe garden eels, with their yellowish

bodies and black spots. The pristine reefs around Goat Island

and Little Tobago were most impressive, as

were the high density coverage and large

variety of colorful hard and soft corals.

I have never found diving elsewhere

in the Caribbean that can favorably compare.

Tropical fish were plentiful: schooling

Creole wrasse, bicolor damselfish,

harlequin bass, doctorfish, stoplight and

princess parrotfish, yellowtail damselfish,

trumpetfish, scorpionfish, yellowhead

wrasse, black durgon and what seemed

like the entire puffer family. Red bearded fireworms up to 12 inches long crept along on most sites. I saw the occasional flamingo tongue and fingerprint cyphoma,

while large nurse sharks roamed or rested at many sites, but I only saw one

black-tip shark. It was off-season for mantas.

The pristine reefs around Goat Island

and Little Tobago were most impressive, as

were the high density coverage and large

variety of colorful hard and soft corals.

I have never found diving elsewhere

in the Caribbean that can favorably compare.

Tropical fish were plentiful: schooling

Creole wrasse, bicolor damselfish,

harlequin bass, doctorfish, stoplight and

princess parrotfish, yellowtail damselfish,

trumpetfish, scorpionfish, yellowhead

wrasse, black durgon and what seemed

like the entire puffer family. Red bearded fireworms up to 12 inches long crept along on most sites. I saw the occasional flamingo tongue and fingerprint cyphoma,

while large nurse sharks roamed or rested at many sites, but I only saw one

black-tip shark. It was off-season for mantas. For the first dive on this side, we moored onto the MV Maverick, which

rests at 100 feet (other dives were around 60 feet). It was the only place

we encountered much current, so I grasped a rope Marvin dangled from the boat

and he pulled me onto the bow for descent. As we slowly finned its three

decks, I wondered whether this intentionally-sunk ferry was worth the effort.

But then ascending from the dark bottom deck into light, it looked as if someone had decorated the railings

for the holidays with white blossoms

of hydroids and corals. Cobias swam

by, as did queen angels; schooling

jacks were in the distance.

Returning to the boat, I removed

my weights and tank, then entered

the boat on my belly, with Marvin's

hefty assist.

For the first dive on this side, we moored onto the MV Maverick, which

rests at 100 feet (other dives were around 60 feet). It was the only place

we encountered much current, so I grasped a rope Marvin dangled from the boat

and he pulled me onto the bow for descent. As we slowly finned its three

decks, I wondered whether this intentionally-sunk ferry was worth the effort.

But then ascending from the dark bottom deck into light, it looked as if someone had decorated the railings

for the holidays with white blossoms

of hydroids and corals. Cobias swam

by, as did queen angels; schooling

jacks were in the distance.

Returning to the boat, I removed

my weights and tank, then entered

the boat on my belly, with Marvin's

hefty assist. Divers Compass: My Tobago package was arranged through Sausan

Shalah at Maduro Dive; e-mail her at

Divers Compass: My Tobago package was arranged through Sausan

Shalah at Maduro Dive; e-mail her at