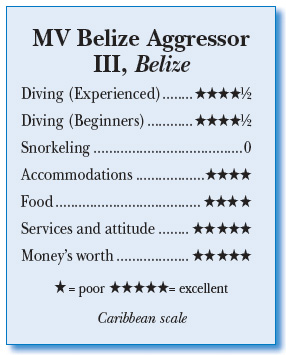

MV Belize Aggressor III, BelizeContents of this Issue: MV Belize Aggressor III, Belize You Won’t Put Down Tropical Ice, A Sensational Scuba Thriller Set In Belize Flies in the Face of Good Business When Sport Divers Meet Spearfishers Atlantis Dumaguete Resort, Negros Island, Philippines Oman Aggressor Continues to Cancel Trips A DAN Survey on Diver Fitness: Is Your Liver as Healthy as your Heart and Lungs? The Lesson Of Walden Pond Or Why Not To Pee Underwater When Diving in the Maldives Disappoints Another Non-Native Species in Florida Scuba Diving Can Be Hazardous to Your Health Will You Be the One to Submit Our 10,000th Reader’s Report? No Side-Mount Tanks on Aggressors? Diving Computer Algorithms Are Important Unvarnished Truth Can Hurt But It’s Still the Truth Oxygen Analyzers – What’s New? Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 good boat, great crew, easy diving from the June, 2018 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Diver, It was a beautiful morning at Amberhead North, on Belize's Turneffe Atoll, perfect for our checkout dive and giving the guides an opportunity to spot any problem divers. In calm water, we had no requirement to stick with the guides, so my buddy and I headed off to explore, eventually returning to the sand patch where we had started. Oddly, the sand sported a fresh drag mark. My partner signaled, "Where's the boat?"

Onboard, there were no complaints, just laughs, which spoke to the good nature of the 17 divers, who were mostly North Americans of a certain age, with the exceptions being two Chinese students from the University of Illinois, a brother and sister from Brazil, and one couple's teenage son. Three newbies were finishing their open water training. Liveaboard divers know there can always be a jerk in the group, but not this time (unless it was I and no one called me out. And where had the Aggressor gone? A crew member speculated that a barge had tied up at their mooring without allowing enough slack in the line and loosened the mooring pin, which set the Aggressor adrift. The Belize Aggressor III is a 110-foot (33m) monohull that can accommodate 18 divers. An over-engineered shuttle boat that once ferried oil-rig crews in the Gulf of Mexico, she has a few minor quirks. While the master stateroom is on the sun deck, most cabins are on the lower deck. We chose one amidships so we would have less movement. It was comfy, without being tight, with room for our luggage under the double bed lower bunk and upon the upper single bunk. There were no wall hooks, probably to discourage divers from hanging wet skins and swimsuits (a nod to preventing mildew). The air-conditioning worked well -- days were a balmy 90°F (32°C) or so -- as did the marine head if you followed instructions: flush early, flush often, and be careful what you put in the bowl. And one quirk: it was hard to hear the diving bell from my cabin and, in fact, I slept through one dive. I had plenty of room to dress up on the spacious dive deck, where I stored small stuff in an underseat bin and hung other gear overhead; crew members cinched weight belts around the hanging wetsuits to prevent them from flying over the side. After gearing up, tank and all, I would back down the five steps to the stern platform, where a crew member helped me with my fins, then with a giant stride, I hit the water. After a dive and a climb up the wide stairs, the crew helped me with my gear, and I'd wash off the salt in one of the two swim platform showers (though the water pressure wasn't always up to snuff). Nightly, they rinsed everyone's rig.

At Turneffe Atoll and Lighthouse Reef (all low-lying, brush- and palm-covered cayes), the corals were healthy and diverse. In early April, the water averaged a cool 76°F (24°C). I spent the week in a 5mm wetsuit, while my partner needed her warm 7mm. Some divers -- especially the younger ones -- claimed to be comfortable in rash guards and board shorts, but I don't know how, especially with long bottom times, once 90 minutes. Visibility was more than 50 feet (15m) on most sites. At Half Moon Caye Wall (Lighthouse Reef), a steep sand slope rose from the wall 50 feet down to 20 feet (6m), where turtle grass harbored lots of conch. While an occasional shark or Goliath grouper cruised by, I became interested in watching hunting southern stingray buddy teams. Stingrays moved slowly along the sand, followed closely by a permit or jack, at times even several grunts, ready to pounce when a fluttering stingray flushed out morsels. A pair of gray angelfish joined the hunt.

On a dive at Quebarca, I eased up to a cleaning station where a dozen neon gobies attended to a 3-foot (1m) great barracuda. The 'cuda seemed unimpressed by me, so I got several good close-up shots, but left feeling like I'd interrupted someone's bath. I'm a casual photographer, happy with a simple point-and-shoot SeaLife DC1400 that I can stuff into my modified BC pocket. I shoot mostly video -- senior eyes and all -- which can drain a battery, so I bring several and charge and change them religiously. The Aggressor's large camera table had electrical outlets on the shelf below, but no air gun. When Captain Jerome -- a professional, friendly and athletic fellow -- spotted me drying my camera with my deck towel, he brought out towels just for us photographers. All the six Belizean crew members were very accommodating. After dives, photographers would gather in the salon or dining to work on photos. The salon features a large flat screen that the crew used for its end-of-week video/slide show and occasionally for movies. I had a real photography challenge when I discovered a collection of blennies on a concrete mooring block. While my buddy had the patience to hover and wait, with less patience (and poorer eyesight), I kept my head up and was rewarded when a sailfin blenny popped from its hole. I maneuvered my camera in close before he pulled back. On a second dive here, I sank into the midst of a silversides' baitball flowing in and out of a coral head crevice, and with my camera running, they closed around me without much fuss. On the sandy bottom below, a lone lionfish drifted by, biding his time before sucking up a snack.

After the Blue Hole, we toured the Half Moon Caye bird sanctuary, a good way to off-gas rather than lounging around the boat. Everywhere, hermit crabs crawled around in their snail shell homes like a convention of mini-Winnebagos. Two men cleaned fish on a wooden bench, tossing scraps to three nurse sharks maneuvering in a foot of water. I climbed an elevated platform to view nesting red-footed boobies while frigate birds soared overhead and iguanas posed for photographers below. Yanis, the friendly yet saucy chef (she reminded me of a favorite aunt that nobody messes with), prepared lots of good food. Breakfasts were eggs to order, pancakes, French toast, or Johnny cakes, and bacon, sausage, or ham, plus toast and bagels, and a large bowl of fruit. Lunches often started with a soup and could be Belizean fare (primarily spicy sautéed meats), hamburgers, tacos, burritos and a yummy taco salad. Before dinner, we divers would gather on the top deck for storytelling and drinks -- wine and beer were complimentary, but best bring your own spirits. Dinners were tasty, on various nights featuring fish, shrimp, pork loin or roast beef, with plenty of fresh vegetables properly cooked. (The sole vegetarian always got something special.) Although I did not partake (much), desserts were reportedly delicious. Between-dive snacks were sometimes sinfully delicious; it was a kick to watch adult divers shoving too-warm chocolate chip cookies into their mouths while hopping around, half out of their wetsuits. At a site called Aquarium, Spots, the resident reef shark with a white patch above and a little behind each eye, swam about, while a squadron of spotted eagle rays swam gracefully along the wall. This seemed to be a home for elderly or perhaps infirm trunkfish.

But, even experienced divers sometimes get ahead of themselves. Divemaster Daniel, a trim and muscular guy, asked one diver, "Is your second stage breathing okay?" The diver was rigged and ready to go. He popped his second stage into his mouth, and when he didn't get any air, he reached back to turn on his first stage, which, it turned out, he had not attached to his tank. It was his bad luck that the whole scene was caught on video, much to our amusement. He had no "habitual" buddy, so there's a lesson there about the benefits of diving regularly with someone, keeping each other out of trouble. I liked the night dives, though they were marred by unsightly bloodworms wriggling through the water. At Long Caye Reef, I watched a Scotch bonnet snail moving around like a mini-Roomba, bumping into things, then changing direction. At Ell Point, I dropped onto a shallow, sandy bottom that was home to many southern stingrays, several giant hermit crabs churning through the sand, a school of arrow squid, and a hunting Spanish slipper lobster. One advantage of diving Belize is that from most U.S. cities, one can get there in a single day. Many flights arrive at Belize City at the same time, making for long, noisy lines at immigration. Be patient, take a deep breath and just go with it. Once through, we had to sit outside in the heat on concrete benches, babysitting our luggage, waiting for other arriving divers before boarding a van to the Radisson Hotel to wait again before boarding the Aggressor (may I whine about the rigors of travel?). All in all, the Belize Aggressor offered a great trip for easy divers, inexperienced divers, any diver without great demands for gangbuster diving. Nothing exceptional, mostly predictable, and a very nice diving getaway. -KM Our Undercover Diver's Bio: KM's interest in diving was sparked watching Jacques Cousteau specials in the '70s. Though he gained an appreciation for boat operations in the Coast Guard, he didn't learn to dive until he moved to the Army, where his instructors felt that hazing was a legitimate educational tool. He has worked as a volunteer drag boat race safety diver, volunteer search and recovery diver, and equipment technician, but regrettably had to maintain a real job until retirement and now spends most of his time goofing off.

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

Earlier, the crew had told us if we surfaced far from the boat, just inflate our BCs and relax, and they will come get us. Knowing we were at the right spot, we surfaced and saw the Aggressor a few hundred yards away, its white hull gleaming in the sun. We bobbed up and down near other buddy teams waiting for a pickup. Soon the Aggressor came alongside, and a crew member threw us a life ring and towed us in.

Earlier, the crew had told us if we surfaced far from the boat, just inflate our BCs and relax, and they will come get us. Knowing we were at the right spot, we surfaced and saw the Aggressor a few hundred yards away, its white hull gleaming in the sun. We bobbed up and down near other buddy teams waiting for a pickup. Soon the Aggressor came alongside, and a crew member threw us a life ring and towed us in.

One morning near Half Moon Caye, I peered out my porthole to see a small boat alongside. Wearing black fatigues, a Belizean park ranger toting an M4 carbine stood by while others wrestled scuba cylinders onto the Aggressor. The crew refills cylinders for the rangers stationed there, a smart way to stay friends with people who can make or break your operation.

One morning near Half Moon Caye, I peered out my porthole to see a small boat alongside. Wearing black fatigues, a Belizean park ranger toting an M4 carbine stood by while others wrestled scuba cylinders onto the Aggressor. The crew refills cylinders for the rangers stationed there, a smart way to stay friends with people who can make or break your operation. Every week, the boat visits

the Great Blue Hole, a prehistoric

cave with a collapsed roof, which

appears as a deep blue hole in the

middle of a light coral plateau

(it was inaccessible by boat until

Jacques Cousteau and his crew

blasted a passageway in the early

'70s). I skipped the 35-minute,

130-foot(40m)drop (coming back

required two stops, one at 70 feet

[21m], one at 15 feet [4.5m]),

and took to the shallows, where

I found sand tilefish, yellowhead

jawfish, Pedersen cleaner shrimp,

tube-dwelling blennies, and a

school of midnight parrotfish. While my buddy was shooting macro, a stingray

buzzed her. We were encouraged to look for headshield

slugs in the turtle grass, but no luck.

Every week, the boat visits

the Great Blue Hole, a prehistoric

cave with a collapsed roof, which

appears as a deep blue hole in the

middle of a light coral plateau

(it was inaccessible by boat until

Jacques Cousteau and his crew

blasted a passageway in the early

'70s). I skipped the 35-minute,

130-foot(40m)drop (coming back

required two stops, one at 70 feet

[21m], one at 15 feet [4.5m]),

and took to the shallows, where

I found sand tilefish, yellowhead

jawfish, Pedersen cleaner shrimp,

tube-dwelling blennies, and a

school of midnight parrotfish. While my buddy was shooting macro, a stingray

buzzed her. We were encouraged to look for headshield

slugs in the turtle grass, but no luck. I chuckled watching one of the young college students push around a camera rig that seemed bigger than she was. On one dive, unbeknownst to her, a remora attached itself to her stomach. Frequently, she would reach down to brush the area, not knowing what was there. The critter would dart way, then quickly return as soon as she went back to shooting. Then she would brush again.

I chuckled watching one of the young college students push around a camera rig that seemed bigger than she was. On one dive, unbeknownst to her, a remora attached itself to her stomach. Frequently, she would reach down to brush the area, not knowing what was there. The critter would dart way, then quickly return as soon as she went back to shooting. Then she would brush again. Diver's Compass: Two divers, standard double cabin, was $5,990 for the seven-night cruise, plus nitrox ($100/person) and port fees ($95/person. The crew hustled and delivered, so we tacked on 15% of the cabin cost, in cash (the most sincere form of flattery) ... Nitrox levels fluctuated early in the week, but they soon stabilized the mix at 32 percent ... Five dives were offered every day but two; four dives on Blue Hole day and two on the last day, beginning at dawn ... they carry a pickup boat in case anyone gets in trouble.

Diver's Compass: Two divers, standard double cabin, was $5,990 for the seven-night cruise, plus nitrox ($100/person) and port fees ($95/person. The crew hustled and delivered, so we tacked on 15% of the cabin cost, in cash (the most sincere form of flattery) ... Nitrox levels fluctuated early in the week, but they soon stabilized the mix at 32 percent ... Five dives were offered every day but two; four dives on Blue Hole day and two on the last day, beginning at dawn ... they carry a pickup boat in case anyone gets in trouble.