WAOW, IndonesiaContents of this Issue: How Diving Inspires This Science-Fiction Writer Bahamas, Hawaii, the Red Sea. . . Lawsuit over Diver Death on San Diego’s Yukon A Win for Shark Fins: Fiji Airways Reverses Its Stance Undercurrent Is Awarded a Grant for Environmental Coverage What Happens to Those Aging Dive Guides? Lost Your PADI Card? How to Avoid the $37 Fee Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 fiery volcanoes, dangerous dragons and colorful diving from the July, 2013 issue of Undercurrent

Dear Fellow Diver: Sixty feet down on my first dive, I quietly admired a barrel sponge the size of a smart car. Tiny white sea cucumbers thrived in every nook and cranny. Then a thundering explosion ripped through the water. I quickly looked at my dive buddy. "What in the world was that?" A thousand thoughts raced through my mind, but I guessed it might just be local fishermen dynamiting. I shrugged it off. Upon returning to the surface some 60 minutes later, I had my answer. A towering mushroom cloud billowed from the lip of a nearby volcanic crater. The tiny island of Palau Palue had just erupted. "Awesome," I thought. "It doesn't get more primal than this." I climbed the ladder into the rigid tender, and the driver returned us divers to the mother craft. Fine volcanic ash rained down on us, covering chairs, tables, stairs, everything. I could not have asked for a more unusual way to begin my 12 days of diving on the luxury liveaboard WAOW.

This voyage, which began in late April, included 10 days of diving off the remote Indonesian islands between Flores and Bali, and a walkabout on the island of Komodo. Yes, Komodo dragons! There's another item I would soon check off my bucket list.

On our dive at Secret Garden, water clarity was excellent -- as much as 100 feet visibility (on some dives it dropped to 30 feet), and the current was nonexistent. This was a macro photographer's ideal environment. Within 10 minutes, I saw beautiful nudibranchs, two fire gobies darting in and out of coral, a pair of signal gobies and a tridacna clam the size of a microwave oven. (I thought of some lost 1950s B-movie, where a solo native diver accidentally sticks his foot into a giant clam and struggles frantically to free himself.) Then my wife excitedly motioned to me. Sitting on a rocky ledge were two giant frogfish, each the size of a loaf of bread (that's huge in the frogfish world). They ignored me as I hunkered down to capture a few frames. (I shoot with a Canon G7 that is going on 10 years old. I occasionally get embarrassed when a 5D Mark III or a D800 is whipped out, but I try to deal with it gracefully.) After all divers surfaced, our tender returned us to the WAOW, where Cindy, our dining room hostess, greeted us with a warm smile and refreshing drink. I peeled off my wetsuit with the help of a deck attendant, who rinsed and hung it to dry, then took a warm shower on deck. I soon fell into a pleasant routine -- rest followed by diving followed by eating. The food ranged from good to excellent. In the morning, pre-dive breakfasts consisted of cereal, milk, coffee, fresh fruit, yogurt and toast. The first dive was around 8 a.m., followed by a substantial second breakfast of fried eggs, bacon, sausage, potatoes, excellent Indonesian stir-fry noodles, pancakes, pastries and fresh fruit. Dive 2 was around 11 a.m., after which came a quick nap in a deck hammock. Lunch, then Dive 3 at 2 p.m., followed by reading in a lounge chair or downloading my photos. Dive 4 was either a sunset or night dive. Lunch and dinner were sit-down affairs: soup or salad, followed by a main course like prawns and rice, a fillet and potatoes, or a fresh fish stir-fry. Regarding desserts, the crowning achievement was a molten chocolate cake that erupted in warm liquid chocolate when I stuck my fork in. The first glass of wine each night was free, and the Fanta, Coke and juice were always complimentary. As the sun set over Gili Banta, I eased into the water for a night dive. My light quickly illuminated a decorator crab moving through the staghorn coral. So bizarre was this crab that had it been human, it would have had a successful career in Paris as a high-fashion runway model. Each leg was adorned with cool stuff, a piece of sponge here, a shiny shell there. Lady Gaga would have been proud. Next up was an anemone about 10 inches tall. Its tubular base was about 1.5 inches thick and about eight inches long. From the top, flowing white tentacles seized a minute morsel, then the tentacle slowly delivered the prize back to the central cluster. Scores of tentacles appeared to move independently of each other. Mesmerized by this creature, I thought how prolific science-fiction writers use their vast imaginations to depict bizarre life forms on distant planets. Their imaginary visions pale in comparison to the reality of what divers see every day.

The Komodo dragon kills with one bite. Its saliva is highly infectious. It typically waits in ambush and inflicts a fatal bite on wild goats, feral pigs and even water buffalo (although it can take up to two weeks for the latter to succumb). Patiently the dragons follow their prey, waiting. I was surprised when a dragon entered the water to swim toward our tender. Jay was less delighted and directed the tender to a safer distance. Jay asked, "Still want to go ashore?" "Perhaps not," I said. Cannibal Rock -- apparently named thus become someone once saw one dragon devouring another -- was an amazing dive. The colors of the soft coral were stunning, massive schools of fish swarmed everywhere, and the reef was pristine and healthy. There were crustaceans, nudibranchs and clownfish frolicking in their anemones. A map puffer and a moray eel shared a cleaning station with dozens of hinge-break shrimp. A sea cucumber slowly marched across a coral head with its bizarre padded feet. The variety of life blew me away. That night, under a sky full of stars, dinner was set up on deck, on two large, hand-made, wooden tables. Afterwards, we rocked the night away to a large selection of music choices. The diverse group of 11 divers -- four from Germany, two from France, four Americans (two living in Paris) and one from Canada -- created even more interesting conversations. (Other nights, the captain joined me for a game of chess.) There was plenty of room to separate myself from the group -- common areas had two upper decks, one with hammocks and the other with reclining chairs. The lower deck had three large tables for outside dining. The indoor dining area had a well-stocked library, bar area and a dedicated photo room with a computer.

By the end of our dive, I had lost count of the number of mantas we saw. We surfaced miles from our entry point, but no sweat. WAOW staff equips each diver with a dive locator. I depressed Button 1, which allowed me to send a voice transmission to the boat captain and the two tenders. (Button 2 would have sent out a distress signal to all boats in the area.). The tender arrived in less than a minute. On the last night, we enjoyed a BBQ on deck under the stars with a menu of steak and prawns, corn on the cob and salad. Afterwards, I took a few notes of the bigger fish I had seen -- dogtooth tuna, Spanish mackerels, giant trevallys, Napoleon wrasse, humphead parrotfish, reef (Manta Alfredi) and giant mantas (Manta Birostris), mobulas, white-tip and gray reef sharks -- then listened to music until 1 a.m. I must repeat that the luxurious WAOW is a first-class operation from start to finish. The entire crew was genuinely friendly and helpful. While the dive locations are very remote and seldom visited, those are the spots that resemble diving like it was elsewhere a generation ago. The reefs are pristine, healthy, vibrant and alive with fish. All I can say is WAOW! -- A.D.

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

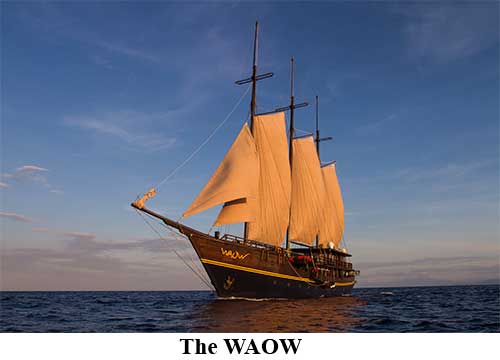

That's an acronym for Water Adventure Ocean Wide.

Just a year old, she is an impressive 197 feet long and

can handle 18 divers in nine spacious, upscale cabins.

When she unfurrows her three great sails, she is truly an

impressive site. Her cabins are top-of-the-line: king or

queen beds, cabinets

and lots of storage

space, full bathrooms

with toilets,

sinks and showers. I

had a desk to set up

my notebook computer

to run on wireless

Internet, and a large

LCD TV with an enormous

selection of movies

and first-run TV

programs (my wife and

I actually watched the

last season of Dexter while on board). And ours was a standard

cabin! Some had private decks and

large view windows.

That's an acronym for Water Adventure Ocean Wide.

Just a year old, she is an impressive 197 feet long and

can handle 18 divers in nine spacious, upscale cabins.

When she unfurrows her three great sails, she is truly an

impressive site. Her cabins are top-of-the-line: king or

queen beds, cabinets

and lots of storage

space, full bathrooms

with toilets,

sinks and showers. I

had a desk to set up

my notebook computer

to run on wireless

Internet, and a large

LCD TV with an enormous

selection of movies

and first-run TV

programs (my wife and

I actually watched the

last season of Dexter while on board). And ours was a standard

cabin! Some had private decks and

large view windows. Each morning, Jay Monney, our

Swiss cruise director and divemaster,

would sing out "dive briefing, dive

briefing, briefing dive." This simple cadence became an infectious tune that

reverberated in my brain for weeks. Jay, an expert photographer, showed dive

diagrams and photos of the critters we might encounter on a large LCD monitor. He had no problem communicating to the diverse divers aboard, effortlessly conversing

in English, German, French and Indonesian (he speaks seven languages).

Our dives were limited to a depth of 90 feet, but at times we dropped below 100

feet with no hassle. We were required to stay with our dive buddy but not with

the guide. The protocol was divers first, followed by still photographers, followed

by videographers. Underwater, Jay and the other guides, Howay (a man) and

Kay (a woman), were quick to find unusual critters. On board, they were quick to

fix problems, such as stopping the free flow from my new octopus or substituting

a fin strap for one that snapped (yes, I failed to check my gear thoroughly

before leaving home). Divers had their own gear boxes to store dive computers,

masks and so forth. I would suit up, don the small stuff and board my dive tender

(five divers traveled in one, six in the other) where the big gear was ready

to go. On the count of three, we all backrolled into the water. I started diving

in a 3-mil but soon switched to just a skin in water that varied between 76

and 86 degrees.

Each morning, Jay Monney, our

Swiss cruise director and divemaster,

would sing out "dive briefing, dive

briefing, briefing dive." This simple cadence became an infectious tune that

reverberated in my brain for weeks. Jay, an expert photographer, showed dive

diagrams and photos of the critters we might encounter on a large LCD monitor. He had no problem communicating to the diverse divers aboard, effortlessly conversing

in English, German, French and Indonesian (he speaks seven languages).

Our dives were limited to a depth of 90 feet, but at times we dropped below 100

feet with no hassle. We were required to stay with our dive buddy but not with

the guide. The protocol was divers first, followed by still photographers, followed

by videographers. Underwater, Jay and the other guides, Howay (a man) and

Kay (a woman), were quick to find unusual critters. On board, they were quick to

fix problems, such as stopping the free flow from my new octopus or substituting

a fin strap for one that snapped (yes, I failed to check my gear thoroughly

before leaving home). Divers had their own gear boxes to store dive computers,

masks and so forth. I would suit up, don the small stuff and board my dive tender

(five divers traveled in one, six in the other) where the big gear was ready

to go. On the count of three, we all backrolled into the water. I started diving

in a 3-mil but soon switched to just a skin in water that varied between 76

and 86 degrees. One afternoon, we went ashore on Rincon Island, a sister island to Komodo,

to photograph the famous dragons. Trained guides escorted us on a two-hour hike.

Only a few dragons were hanging out by the camp kitchen, asleep in the sun. Jay

said not to worry, he knew a secret spot, so we boarded the tender and headed

for a remote beach. As we neared shore, I spotted two dragons about six feet in

length. When our tender approached, they sprinted with amazing speed toward us.

This commotion caught the attention of two larger dragons, perhaps nine feet

long, that were hiding in the bushes. They too bolted with alarming speed toward

us. I looked at the eyes of one of these prehistoric creatures; there was no

fear in there. He was the top predator on this island and I was the prey.

One afternoon, we went ashore on Rincon Island, a sister island to Komodo,

to photograph the famous dragons. Trained guides escorted us on a two-hour hike.

Only a few dragons were hanging out by the camp kitchen, asleep in the sun. Jay

said not to worry, he knew a secret spot, so we boarded the tender and headed

for a remote beach. As we neared shore, I spotted two dragons about six feet in

length. When our tender approached, they sprinted with amazing speed toward us.

This commotion caught the attention of two larger dragons, perhaps nine feet

long, that were hiding in the bushes. They too bolted with alarming speed toward

us. I looked at the eyes of one of these prehistoric creatures; there was no

fear in there. He was the top predator on this island and I was the prey. One day we dived Manta Alley, which didn't live up to its name. Though

absent of mantas, it was still a beautiful dive. However, on another morning,

we made a drift dive at Makassar, off Komodo Island. I backrolled off the tender

in sync with the group, but the stiff current grabbed me straight away.

My dive buddy grabbed the collar of my BC and held on for dear life. Our dive

guide and two other divers were about 50 feet away, so I signaled to my buddy to

make our way toward them. It was futile. The current had us in its grip, and we

were going wherever it was taking us. Howay, our dive guide, rapidly faded from

site. We descended to 60 feet so that we were hovering about 10 feet off the sea

floor. Now I could see how fast we were flying. I let go, relaxed, embraced the

current and went with the flow. It was exhilarating. I grabbed my buddy's arm to

get her attention and pointed to a shape 65 feet away. It was a huge manta ray

with its mouth open, feeding in the fast current. As it receded into the distance,

two more appeared just 30 feet away. Then came mantas number four, five

and six. My buddy squeezed my arm and pointed straight down. Just six feet below

us, a gigantic manta with a wing span of at least 15 feet, hovered effortlessly

in the current.

One day we dived Manta Alley, which didn't live up to its name. Though

absent of mantas, it was still a beautiful dive. However, on another morning,

we made a drift dive at Makassar, off Komodo Island. I backrolled off the tender

in sync with the group, but the stiff current grabbed me straight away.

My dive buddy grabbed the collar of my BC and held on for dear life. Our dive

guide and two other divers were about 50 feet away, so I signaled to my buddy to

make our way toward them. It was futile. The current had us in its grip, and we

were going wherever it was taking us. Howay, our dive guide, rapidly faded from

site. We descended to 60 feet so that we were hovering about 10 feet off the sea

floor. Now I could see how fast we were flying. I let go, relaxed, embraced the

current and went with the flow. It was exhilarating. I grabbed my buddy's arm to

get her attention and pointed to a shape 65 feet away. It was a huge manta ray

with its mouth open, feeding in the fast current. As it receded into the distance,

two more appeared just 30 feet away. Then came mantas number four, five

and six. My buddy squeezed my arm and pointed straight down. Just six feet below

us, a gigantic manta with a wing span of at least 15 feet, hovered effortlessly

in the current. Divers Compass: My 12-day trip was a pricey $5,604 per person;

Nitrox was available . . . When arriving at an Indonesian airport,

you must obtain a 30-day visa for $25 . . . Flights from

the U.S. to Asia take 10 to 14 hours, then there is another set

of flights to get to Bali, so next time, I will bring a selection

of movies and a good book . . . Website -

Divers Compass: My 12-day trip was a pricey $5,604 per person;

Nitrox was available . . . When arriving at an Indonesian airport,

you must obtain a 30-day visa for $25 . . . Flights from

the U.S. to Asia take 10 to 14 hours, then there is another set

of flights to get to Bali, so next time, I will bring a selection

of movies and a good book . . . Website -