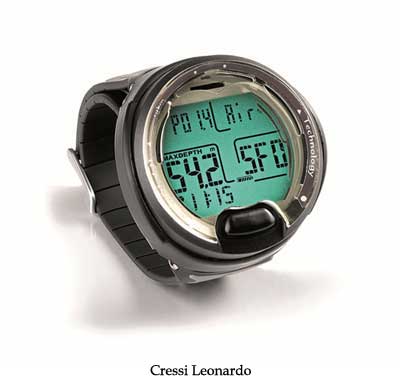

A Computer for Non-Techie DiversContents of this Issue: Rendezvous Dive Adventures, British Columbia Dive Stores in the Internet Age Did This Divemaster Commit Suicide, or Was She Silenced? Raja Ampat Liveaboard Goes Down in Flames Still Unclear How Key Largo’s Get Wet Got Wet A Computer for Non-Techie Divers How Divers Can Give Back: Part I Loving the Chambered Nautilus to Death Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 the $350 Cressi Leonardo from the February, 2012 issue of Undercurrent

It seems like only yesterday that I was commissioned by a British magazine to write an article explaining the advantages of diving with a computer. That was 25 years ago, and the computer I had then cost $600, which was a lot of money in those days. It was such a flamboyant display of wealth that other divers - - total strangers - - would try to rip it off my wrist at dive sites with the excuse that computers were dangerous and I should stick to tables, watches and depth-gauges like the rest of them. Of course, it was really the cost that offended them. Today, few divers would consider diving without one computer and many even use a second one as backup. They have become so relatively cheap that nearly every serious diver can afford to do that. The manufacture of diving computers originally fell to a couple of companies. In Europe, diving computers bearing different brands all came from the same factory in Switzerland. Then that Finnish upstart Suunto got in on the act, although it stayed firmly with everything under its own label. In America, one of Bob Hollis' companies dominated the computer market, manufacturing for many different brands as well as Oceanic and Aeris. Companies that wanted something different went to Seiko in Japan, a company that made no computer under its own label but was happy to manufacture for others. The diving business is very small. I was once told that the entire annual production of current European brand-leader Suunto by units only equalled 10 minutes of Nokia's cell phone production (a lot more people use phones, obviously). Similarly, Seiko makes a lot of products, and I'm told it no longer has an interest in the small world of diving computers. This left companies that relied on Seiko supplies out in the cold. Cressi, in Italy, was one of them. Not daunted, Cressi decided to source its own unique product locally. The Cressi Leonardo is it. The Algorithm

Before any geeks write in to say that this is not a proper RGBM, I would like to mention that when the great physicist was questioned about this, he answered that it would only be possible to write a pure RGBM if it was also possible to miss out on the shallow part of the dive. Obviously, that is not possible. The algorithm takes into account silent micro bubbles that might form the nuclei of symptomatic bubbles during a second dive or series of dives. The Instrument The Leonardo's LCD face measures 1.8 inches in diameter, and is hidden behind a protective layer of transparent plastic. It has a strap long enough to go round any wrist clad in a drysuit cuff, while being easy to replace should it be necessary. It is set up using a single button, which is pressed in sequence to access the various menus. When adjusting any part such as the nitrox setting, one must be careful not to overshoot because it is slightly irritating to have to work all the way round again. When I first set it up, there was some frantic button-pressing accompanied by one or two harsh words, but then, I do tend to be impatient. In the Water At a time when Internet forums on diving are full of recommendations to buy technical diving computers on the basis of "you're going to need one, one day," it was refreshing to get into the water undaunted by my own possible lack of technology skills. This computer is designed for use by those who want to go leisure diving and enjoy other reasons for being underwater than using the gear. It proved straightforward to use, gave clear information, guided me when I was probably better off pausing for a minute or two at depth on the way up, gave a clear indication of remaining no-stop time or deco requirements, and beeped at me if I went up too quickly. It indicated clearly the safety stop time, and if I needed to see the screen more clearly in the dark, pressing a button switched on its own backlight. Unsurprisingly, the information it gave regarding deco requirements during the dive were not dissimilar to that given to me by the Suunto (also using a Wienke RGBM) alongside it, including the option to enable deep stops and a variable safety setting. What more do you want? Of course, if you are one of those people who like to do six dives per day, the RGBM might punish you with shorter and shorter no-stop times. If you tend to be more European in your style of diving with, say, only three longer and possibly deeper dives in a 24-hour period, you'll find this computer will be ideal. You cannot program in your own gradient factors or your own algorithm -- Bruce Wienke, in his infinite wisdom, has done that for you. Buy it, set it, strap it on and go diving. After the Dive Finally, for someone who works in media, what a pleasure it was to find that the computer interface and software for the Leonardo was equally at home on either a PC or a Mac. Times are tough, and Cressi has brought this Wienke-type computer to the market at a fiercely competitive $350 list price. I imagine we'll be seeing a lot of them at dive sites before long. John Bantin is the technical editor of DIVER magazine in the United Kingdom. For 20 years, he has used and reviewed virtually every piece of equipment available in the U.K. and the U.S., and makes around 300 dives per year for that purpose. He is also a professional underwater photographer. |

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.

Where do dive computer manufacturers mostly go today for algorithms? One man has grabbed the limelight.

When he's not busy working on nuclear weapons at Los Alamos,

NM, Bruce Wienke likes to write decompression software for the leisure

diving industry. To my knowledge, he has done this for Suunto,

Mares and Atomic, and now he has written a nine-tissue version of his

Reduced Gradient Bubble Model (RGBM) algorithm for Cressi.

Where do dive computer manufacturers mostly go today for algorithms? One man has grabbed the limelight.

When he's not busy working on nuclear weapons at Los Alamos,

NM, Bruce Wienke likes to write decompression software for the leisure

diving industry. To my knowledge, he has done this for Suunto,

Mares and Atomic, and now he has written a nine-tissue version of his

Reduced Gradient Bubble Model (RGBM) algorithm for Cressi.