New Advice for Divers Caught in Rip CurrentsContents of this Issue: Bruce Bowker’s Carib Inn, Bonaire A Good Reason for Car Rental Insurance Belize, Palau, South Carolina and More Diver’s Death Blamed on Few Skills and Faulty Valve Disabled Diver Sues DAN and Coast Guard for Negligence New Advice for Divers Caught in Rip Currents Calculate Your Carbon Fin-Print Breathing Exercises For Longer Dive Time Underwater Photo Tips From the Pros: Part I Diving Pioneers and Innovators Tell All In New Book Editorial Office: Ben Davison Publisher and Editor Undercurrent 3020 Bridgeway, Suite 102 Sausalito, CA 94965 from the October, 2007 issue of Undercurrent

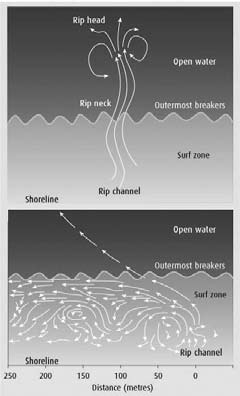

The standard advice to shore divers about escaping a rip current, sometimes wrongly called an undertow, has been doled out for decades: Swim parallel to the shore. Yet rips remain a real danger. In the U.S. alone they contribute to 100 drownings a year, and there’s no end to the anxiety a diver faces if caught in one. Oceanographers have little first-hand experience with rip currents, so a research team led by Tim Stanton and Jamie MacMahan spent a month on the beach studying rips. They even swam directly into the rip, then relaxed and waited to see where they would end up. Conventional wisdom was that a rip was like a straight-sided river gushing out to sea for hundreds of feet, eventually petering out in a floret of small eddies called the rip head. But the researchers found that rip currents can drag objects nearly a half of a mile from shore at speeds of up to 500 feet per minute -- fast enough to overpower the strongest of swimmers. They are especially common on sandy beaches, where waves approach at right angles, and sheltered beaches because the headlands diffract arriving waves in just the right way. The team released GPS-equipped drifters into the waves. They bobbed close to shore for a few minutes, then, one by one, slipped into the rip current. Thirty seconds later, they were 300 feet from shore. Shortly before the surf zone gave way to open water, the drifters turned sharply to the left and then doubled back on themselves. Caught in a rip that looks less like a river than a whirlpool, a swimmer who heads parallel to shore won’t necessarily get out of the current. Rips can pulse from sluggish to fierce in the blink of an eye. The best way to escape a rip may be to rely on the eddies to sweep you back into shallow water. To demonstrate, MacMahan floated into the rip. After heading out nearly to the breakers, he swept southward, parallel to the beach. Not long afterwards, he was back in the shallows. He had been in the rip for four minutes. Had MacMahan battled the current, he might have stayed in place for a minute or two before the rip exhausted him. Then he would have been in real danger, as breaking waves made it hard to catch his breath without choking. Instead, the current carried him safely back home. It won’t always work, but remember it the next time you feel the pull of the ocean. It might just save your life. A version of this article appeared in the magazine New Scientist.

Rip currents were once seen as simple torrents of water surging through the surf zone into open water (top image). That model is now being challenged by real measurements (bottom image).

|

I want to get all the stories! Tell me how I can become an Undercurrent Online Member and get online access to all the articles of Undercurrent as well as thousands of first hand reports on dive operations world-wide

| Home | Online Members Area | My Account |

Login

|

Join

|

| Travel Index |

Dive Resort & Liveaboard Reviews

|

Featured Reports

|

Recent

Issues

|

Back Issues

|

|

Dive Gear

Index

|

Health/Safety Index

|

Environment & Misc.

Index

|

Seasonal Planner

|

Blogs

|

Free Articles

|

Book Picks

|

News

|

|

Special Offers

|

RSS

|

FAQ

|

About Us

|

Contact Us

|

Links

|

3020 Bridgeway, Ste 102, Sausalito, Ca 94965

All rights reserved.